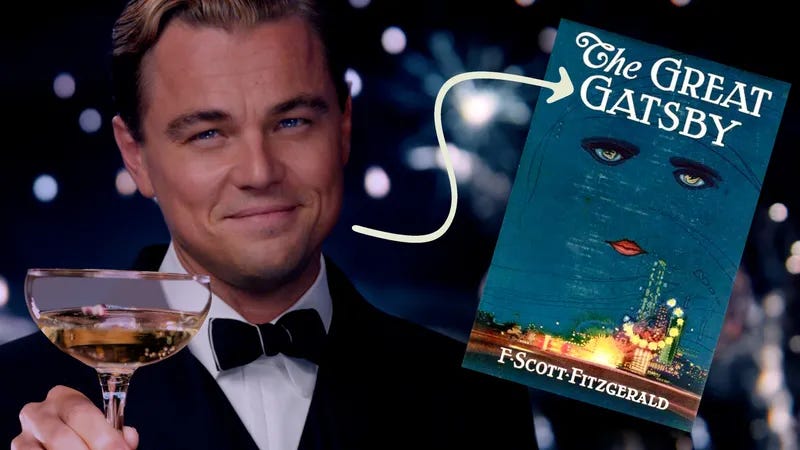

The Great Gatsby at 100

In the Age of Trump what does Fitzgerald's masterpiece tell us about society and ourselves.

F Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby was published 100 years ago today. Very few books endure for 100 years. But Gatsby seems not only relevant but prescient. The first thing to say is it is a beautifully written book. It’s a short book. The language is clear and compact which helps propel the narrative. Yet the language is so vivid that almost every page has a sentence or phrase which jumps off the page and leaps into your memory. The themes of love (lost), wealth (questionably acquired) and personal reinvention (of both Fitzgerald and Gatsby) all set in the elite WASP scene of New York have particular salience with Trump returning to the White House. For Gatsby’s opulent mansion think Mar-a-Lago. Or Trump rallies where strangers attend, as strangers attended Gatsby’s parties, in the hope of a glimpse of the man himself.

The novel is set in the summer of 1922 and tells the story of Jay Gatsby, a man of incredible wealth and many mysteries. He is, among other nefarious business activities, a bootlegger in the age of prohibition. If the novel was written today he would be a drug trafficker. The novel is drowning in prohibited alcohol in much the same way as proscribed cocaine is everywhere today. Following a war time romance with the love of his life, Daisy, he returns post-war, not only with new found wealth but also with a new identity. Poor James Gatz has become rich Jay Gatsby. He settles in New York to rekindle his love affair with Daisy. Who has since married Tom Buchanan. Tom is wealthy but not like Gatsby. He is from an elite, privileged family. His money is not new, it is old.

Gatsby’s attempts to impress and convince Daisy to leave Tom are ultimately doomed. Daisy doesn’t just want to be rich, she wants to be a Buchanan. Later, driving Gatsby’s car, she kills Tom’s mistress, Myrtle Wilson. Then abandons Gatsby to take the blame. Tom lets Myrtle’s husband believe Gatsby was driving. The vengeful husband shoots Gatsby dead before killing himself. It is a tale of someone losing their integrity in pursuit of wealth. Wealth being a destructive force in the novel. Beguiling people like Gatsby (and Fitzgerald and his wife Zelda) before they realise the heavy price they must pay for their illusion. It is also an insight into a segment of society and a period (which Fitzgerald coined ‘The Jazz Age’) where old and new money clash, law and lawlessness meet and glamour and waste abound. Fitzgerald was both in that world and an outsider. As he has Carraway say “I was within and without, simultaneously enchanted and repelled by the inexhaustible variety of life.”

Myrtle and Gatsby are both using different approaches to achieve the same thing. Namely to marry a Buchanan. To upend the established order. While Fitzgerald has Myrtle attempting to ‘marry up’ in a fairly basic way. He has Gatsby taking a more sophisticated route. Gatsby believes if he acquires great wealth (by whatever means possible because unlike Buchanan he is not born into it) he will be able to get the girl. In other words he equates the accumulation of wealth with happiness. Daisy, who’s voice is said to be ‘full of money’, rejects Gatsby because she recognises, what he doesn’t, that the power and influence that comes with old money is power and influence of a different kind than gangster Gatsby can buy with his new money.

Just last week the leaders of Scotland’s political class made the trip to New York to celebrate, if that is the correct word, ‘Tartan Week’. Where they made great efforts to ‘sell’ Scotland to US corporations. This made me think of The Great Gatsby. At the beginning of the book the narrator, Nick Carraway, tells us his family ‘tradition’ is that they are ‘descended from the Dukes of Buccleuch’. However, he then reveals his family actually ‘came here in fifty-one’. This is the real family history, not the myth, not the ‘tradition’. Arriving in 1851 from Scotland suggests the Carraways are refugees from the second wave of Highland Clearances. Rather than connected to the aristocracy. They are not, in fact, from the same class as the Buchanan family. Which is a family name with Scottish origins. And Gatsby’s mansion is said to have ‘an Adam’s study’ in reference to Scottish architect and interior designer Robert Adam.

As the politicians in New York last week were quick to point out Donald Trump’s mother was Scottish. While Vice President, JD Vance, describes himself as “a Scots-Irish hillbilly at heart'“. In his memoir, Hillbilly Elegy, Vance makes it explicit that he rejects the WASP identity on class grounds. Fitzgerald’s Scottish references should be viewed in context of the Scotland’s historical links to the US. Other US writers such as William Faulkner and Edgar Allan Poe also make use of more personal Scottish connections. When Vance talks about these islands we should view his comments through that complicated nexus of history, culture, power and race. The outworking of end of the British Empire. A history of conquest, dispossession, violence and discrimination. Vance and Trump are Britain’s past returning like a spectre haunting modern day Scottish and UK politics.

The references to wealthy British elite families and institutions (such as Gatsby’s claim to be an ‘Oxford man’) matter in the novel. Race and nationalism feature from the first chapter when Tom Buchanan discusses “Goddard’s The Rise of the Colored Empire”, a book clearly referencing Lothrop Stoddard’s 1920 book, The Rising Tide of Color: The Threat Against White-World Supremacy. Tom says to Nick that everyone should read the book because “if we don’t look out the white race will be–will be utterly submerged.” Tom justifies his bigotry on the basis of science, “Well these books are all scientific. . . . This fellow has worked out the whole thing.” After his rant Nick describes Tom “flushed with his impassioned gibberish he saw himself standing alone on the last barrier of civilisation.” We might think of Trump and those promoting replacement theory today. We might also think of Scottish ethnologist Robert Knox. The 19th century Edinburgh University professor infamous for his role in the Burke and Hare scandal. Whose 1850 book The Races of Men espouses an early version of the same scientific racism. Knox has been described as the father of modern racism. He didn’t get a mention on Tartan Day. I don’t think.

The Great Gatsby has many symbols and layers. For example, between Manhattan and the Gatsby mansion on West Egg lies the ‘valley of ashes’. While the ash dumps were a feature of that part of New York, they also represent a nod to TS Eliot’s The Waste Land. Eliot enjoyed The Great Gatsby describing it as “the first step that American fiction has taken since Henry James.” Similarly when a nightingale sings in the Buchanan’s garden it is speculated it might have travelled on an ocean liner. Because nightingales are not native to New York. More likely Fitzgerald introduced the nightingale from Keats. The title of his next novel, Tender is the Night, is from Keats’ Ode to a Nightingale.

His friend Malcolm Cowley, in an introduction to his stories, said “It was not his dream to be a poet, yet that is how he started and in some ways he remained a poet primarily. He said of himself, “The talent that matures early is usually of the poetic type, which mine was in large part.” His favourite author was Keats, not Turgeniev (sic) or Flaubert.” Adding that Fitzgerald had said he was unable to read Ode to a Nightingale without tears in his eyes.

At the end of the book the last man standing is Tom Buchanan. His troublesome mistress is dead, her husband is dead and his wife’s obsessive former lover and rival is dead. We might again think of Trump or Musk when Fitzgerald tells us “They were careless people, Tom and Daisy- they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made.” Old money, power and connections prevail. Nobody attends Jay Gatsby/James Gatz’s funeral. The established order survives.

The Great Gatsby has one of the most famous endings in literature. Just as Gatsby had looked from his mansion across the water at the green light on Daisy Buchanan’s dock and hoped and longed for love, happiness and a great future. Carraway imagines the Dutch sailors arriving and looking at the “fresh, green breast of the new world” as they approach New York. A new land full of possibility, unspoiled. It is telling Fitzgerald uses the Dutch arrival not the British. This is the mercantile class landing, not the Puritans. This is a Paradise Lost. Gatsby and Daisy could be John Milton’s Adam and Eve. The American Dream has turned into a nightmare. Spiritualism replaced by capitalism. The potential, hoped and longed for, obliterated by man’s obsession with power and profit fuelled by domination and exploitation. John Williams novel Butcher’s Crossing develops this theme brilliantly and savagely. Where wilderness is turned to a man-made waste land and souls are turned into the same.

Indeed the last line of Butcher’s Crossing, “he rode forward without hurry, and felt behind him the sun slowly rise and harden the air”, echoes the last line of The Great Gatsby. Where Carraway says “So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.” Hope, then, but only a little.

Perhaps in the Age of Trump it is one of Fitzgerald’s contemporaries who better sums up our time. Eugene O’Neill’s The Iceman Cometh also has a boozy New York setting. (Both O’Neill and Fitzgerald were alcoholics). Not the grandeur of Gatsby’s mansion but Harry Hope’s Saloon in Greenwich Village. A rundown bar populated by rundown people. “It’s the No Chance Saloon. It’s Bedrock Bar, The End of the Line Cafe, the Bottom of the Sea Rathskeller!’

It is here, in Hope’s Saloon, people gather to drown their sorrows and their ‘pipe dreams’. When an assistant pointed out to O’Neill that the ‘pipe dream’ idea had been repeated eighteen times in the play, O’Neill replied “I intended it to be repeated eighteen times!” O’Neill rejects ‘pipe dreams’ and false prophets and false hopes, and he rejects Gatsby’s belief that “tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther.” At the beginning of the play O’Neill sets out his stall.

LARRY: (Grinning) I’ll be glad to pay up – tomorrow. And I know my fellow inmates will promise the same. They’ve all a touching credulity concerning tomorrows. (A half-drunken mockery in his eyes) It’ll be a great day for them, tomorrow – the Feast of All Fools, with brass bands playing! Their ships will come in, loaded to the gun-wales with cancelled regrets and promises fulfilled and clean slates and new leases!’

Isn’t that Trump? Isn’t that Starmer? Isn’t that Tartan Week? Tomorrow.

Your support is invaluable. If you enjoyed the articles and podcasts, I would greatly appreciate if you subscribed to a monthly/yearly pledge to support my work.

Alternatively, you can tip here: buymeacoffee.com/solidaritynotcharity

Don’t forget to join me on Substack Notes.